On the last Sunday of April at 5:30 am, while it was quite dark, I drove into the parking lot of the Kansas Wetland Education Center in Great Bend, where I met up with Curtis Wolf, the manager of the Center. I hopped into his truck and he drove to a piece of private land where there’s a prairie chicken lek just a short hike from a dirt road. The landowner has allowed the Education Center to set up a blind so they can bring people in to see displaying Greater Prairie Chickens. The extended drought has taken a toll on these stunning birds, so the lek had far fewer birds than last year, and this is late in the displaying season. Only two were booming a few days before, and a coyote apparently dispatched one. But the remaining one was already there when we arrived, booming and cackling and dancing, all alone. There was something so achingly poignant, yet so endearingly plucky, about this bird putting his entire being into a performance directed to no one at all.

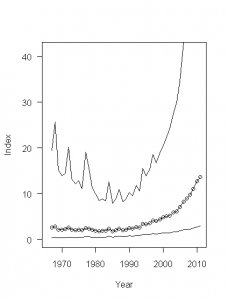

The very first Greater Prairie-Chickens I ever saw, in 1976, were the dwindling remnants of the last population anywhere in Michigan—a population that died out entirely a few years after I saw them. Populations in most places continue to decline dangerously. Kansas is one of the few places where they’ve been increasing in recent years—they’re now at higher levels than they’d been at when the Breeding Bird Survey began in 1966.

Their numbers still are, of course, orders of magnitude less than before pioneer days, but some people are doing their best to ensure that prairie chicken populations have what they need to regain sustainable levels, and the Kansas Wetlands Education Center is at the forefront of efforts to raise public awareness of this splendid bird that has so much cultural and historical significance to Americans as well as being a splendid bird in its own right. There are more successful leks in The Nature Conservancy Preserve at Cheyenne Bottoms, but those are too far from roads to provide viewing options for the public.

Prairie grouse—that is, the two species of prairie chickens, the two sage grouse, and the Sharp-tailed Grouse—have been declining dramatically since so much of the prairie habitat was destroyed for cultivation, cattle grazing, settlement, and energy and mineral exploitation. The Dust Bowl, which killed tragic numbers of humans whose lungs got clogged with powdery dust, killed untold numbers of wildlife, who had no houses to close themselves off from dust storms, and didn’t have hankies or neckerchiefs to cover their mouths during the worst of it. And the soil blowing away left nothing behind for the plants they needed for food or shelter. The government’s focus during and after that devastating decade was naturally on helping farmers find better ways of tilling the land without losing so much to erosion, but no one ever questioned the value of putting into cultivation as much land as people could buy up.

This lek, on private rangeland, has been declining ever since the drought began. The patch used for dancing is overgrazed, but prairie chickens don’t mind dancing on bare ground. The problem is that much of the surrounding habitat, where the grouse spend their lives, has also been overgrazed. The drought has killed so much of the remaining vegetation that a dangerous amount of the land’s surface is exposed soil. Without plentiful rain soon, much of this land may be getting back into Dust Bowl conditions.

Yet one prairie chicken continues to dance and boom on his old lek. People who grew up with trees don’t find prairies as intrinsically beautiful and valuable as forests, but to prairie chickens they’re everything.