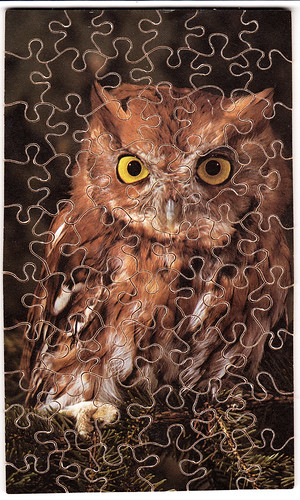

In June, I took the Auto Road tour up Mount Washington in New Hampshire to see a Bicknell’s Thrush for my Conservation Big Year. This rare bird has one of the most restricted breeding ranges and wintering ranges of any bird species found in the entire United States. It breeds in the Catskills, White Mountains, and Green Mountains of New England, at an average of about 4,200 feet in elevation. The vegetation is so thick where it nests that ornithologist George Wallace wrote of it in 1939, “Only a freak ornithologist would think of leaving the trails [on Mt. Mansfield] for more than a few feet. The discouragingly dense tangles in which Bicknell’s Thrushes dwell have kept their habits long wrapped in mystery.”

Bicknell’s Thrush’s winter range is limited mostly to broadleaf forests in the mountains of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Smaller numbers winter in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica.

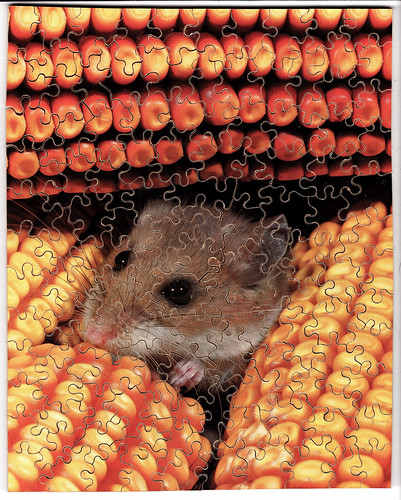

Because Bicknell’s Thrush is so rare and so little is known about it, scientists have been studying every part of its life cycle in an effort to ensure that it won’t become any rarer, because the bird faces many critical issues. Researchers from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Vermont Center for Ecostudies have learned that the rat population on the thrush’s wintering grounds on Hispaniola is huge, and that these rats climb up trees and feed voraciously on roosting birds at night. During a 2009 study, they put radio transmitters on 53 Bicknell’s Thrushes, and rats killed 5 of them—almost 10 percent.

Other studies have been tracking the amount of mercury in the blood of Bicknell’s Thrush. Mercury is a known problem in the northeastern United States, where airborne industrial pollutants are causing more and more problems, especially at the high elevations where Bicknell’s Thrushes breed. It takes only a month or two for mercury levels to drop off, so researchers from the Cornell Lab, the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, and Syracuse University weren’t expecting to find high mercury levels of birds on Hispaniola in winter. But a 6-year study revealed that during winter, the mercury levels of Bicknell’s Thrushes didn’t drop off at all—indeed, they had more than 2.3 times as much mercury in their system on Hispaniola as they do on their breeding grounds! The researchers found that Ovenbirds and some other songbirds had even higher levels, and learned that songbirds in Hispaniola cloud forests had 2–20 times as much mercury as those in lower-lying rainforests. The lead author of the study, Jason Townsend, said that the pervasive fog in cloud forests provides the wet conditions that favor atmospheric mercury’s transformation into more lethal methylmercury, and noted that birds eat more invertebrates and less fruit in the cloud forest than in the rainforest below, resulting in cloud-forest birds taking in higher doses of mercury via their food than rainforest birds do.

Industry pumps about 2,300 metric tons of mercury into this planet’s air every year. Getting mercury out of the air we breathe and the water we drink would be even more difficult than eradicating the rats from Hispaniola—and both problems are so big and so deep and so tall that we’d need to focus extraordinary levels of national and international attention if we were ever to find solutions. Yet right now we’re not even looking seriously for solutions to climate change, which is also impacting Bicknell’s Thrush and other songbirds. During an unprecedented heat wave while the national treasure of Yosemite is on fire, as we enter yet another military engagement, while any search of the news reveals that new oil spills, big and small, are happening every week, it would be impossible for Americans to muster any concern at all about a bird virtually no politicians or voters have even heard of. Coal miners knew that they had to carefully nurture and protect their canaries for the little birds to be used effectively to warn of imminent danger to them all. Now we’re squandering songbirds—our own canaries-in-the-mine—as if the dangers they face weren’t threatening us humans as well.

John Burroughs wrote about Bicknell’s Thrush in 1904, “The song is in a minor key, finer, more attenuated, and more under the breath than that of any other thrush. It seemed as if the bird was blowing in a delicate, slender, golden tube, so fine and yet flute-like and resonant the song appeared. At times it was like a musical whisper of great sweetness and power.” It’s crushingly sad and frightening for me to realize just how few Americans would even notice if that musical whisper were silenced forever.

I posted some basic information about Bicknell’s Thrush in my June 17 blog post.